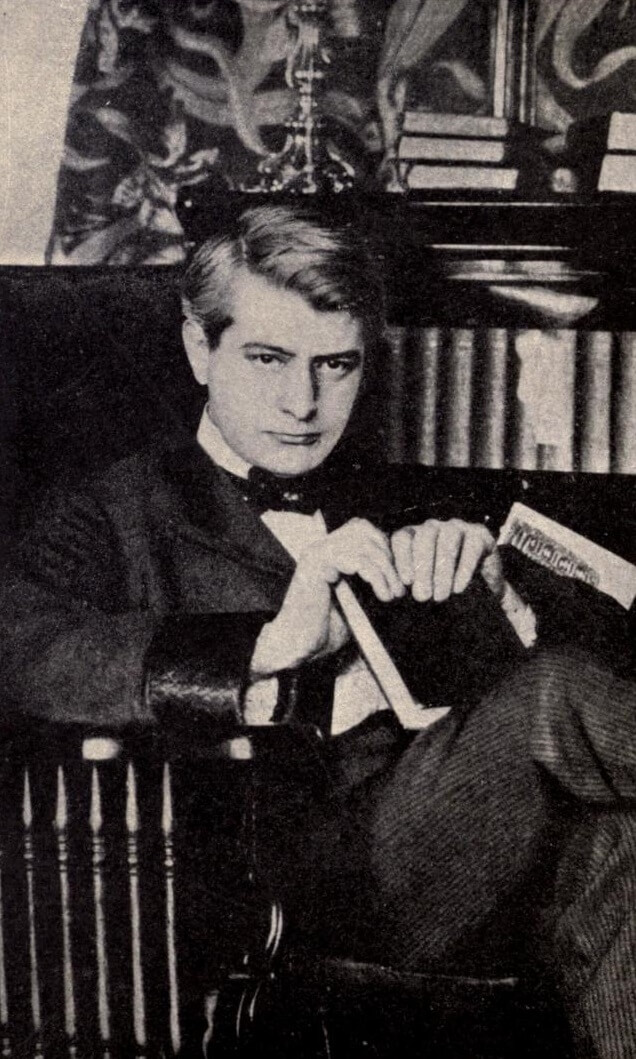

Frank Norris at Age 10

"He would have liked to graduate but did not wish to apply himself to things he did not like, especially mathematics."

Quote about Frank Norris from UC Berkeley Professor

Frank Norris's path to UC Berkeley wasn't as linear as his counterparts; he switched schools frequently as a boy, likely because he struggled with his mathematics courses - it has even been suggested that he may have had a learning disability.

When he was fourteen, his family moved from Chicago to San Francisco, where Norris briefly attended school, only to then apply for art school in Paris.

He spent two years living independently in Paris before coming back to California, realizing that it wasn't painting that excited him, but writing.

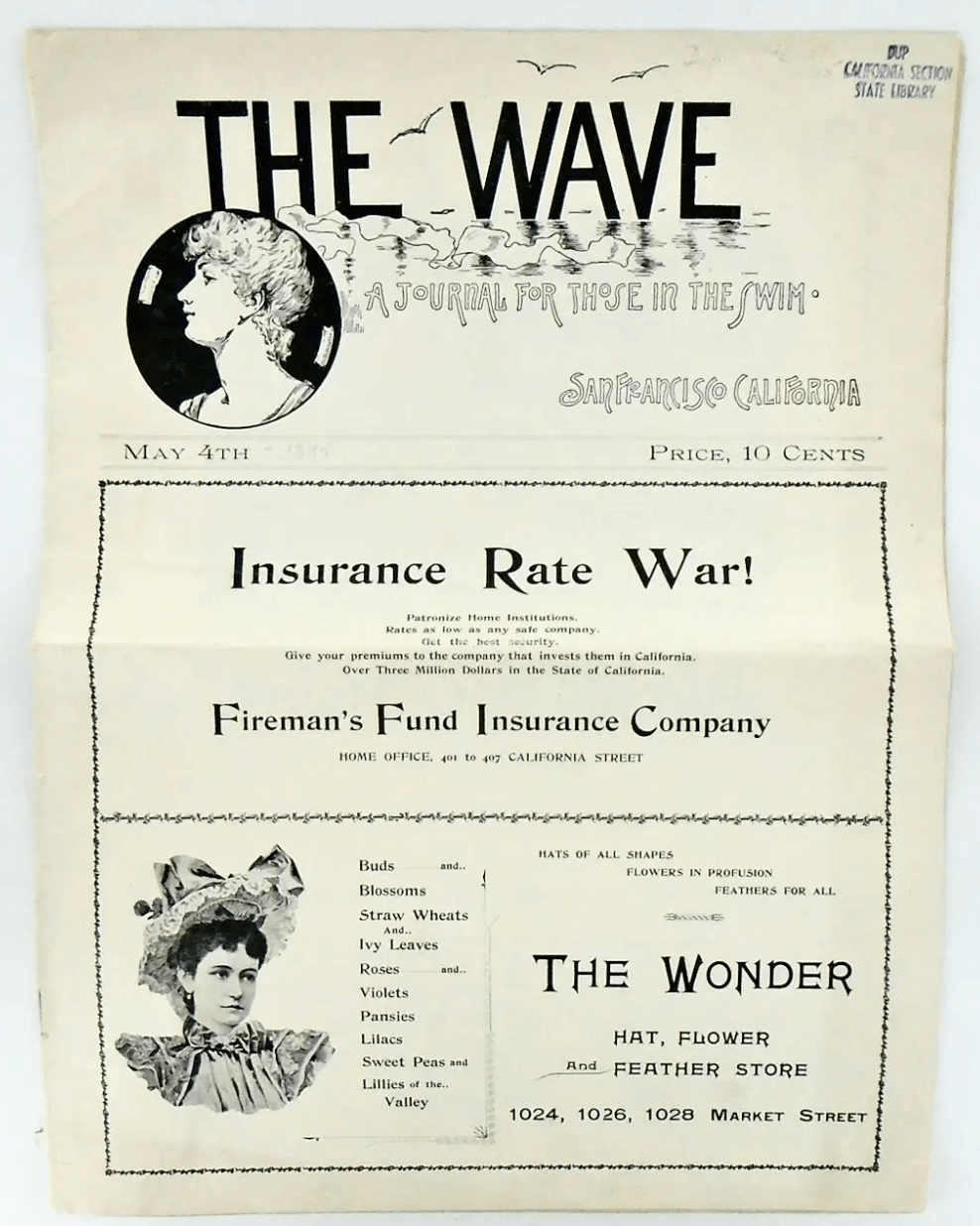

In 1890, Norris was admitted into UC Berkeley. He started writing for The Wave, a San Francisco magazine, where he captured the spirit of the developing city by interviewing locals and providing informative articles. During this time, he started writing one of his famous works, McTeague, taking inspiration from his observations of working class San Franciscans.

Despite his later success as an author, Norris never completed college - despite his best efforts. His inability to do math continuously came back to haunt him.

He believed the university should allow him to choose his own coursework, reasoning that he wanted to become a writer and the interference of taking math courses was “detrimental” to his plan. He transferred to Harvard University in 1894, but he still unfortunately did not graduate.

All Hail the Pig!

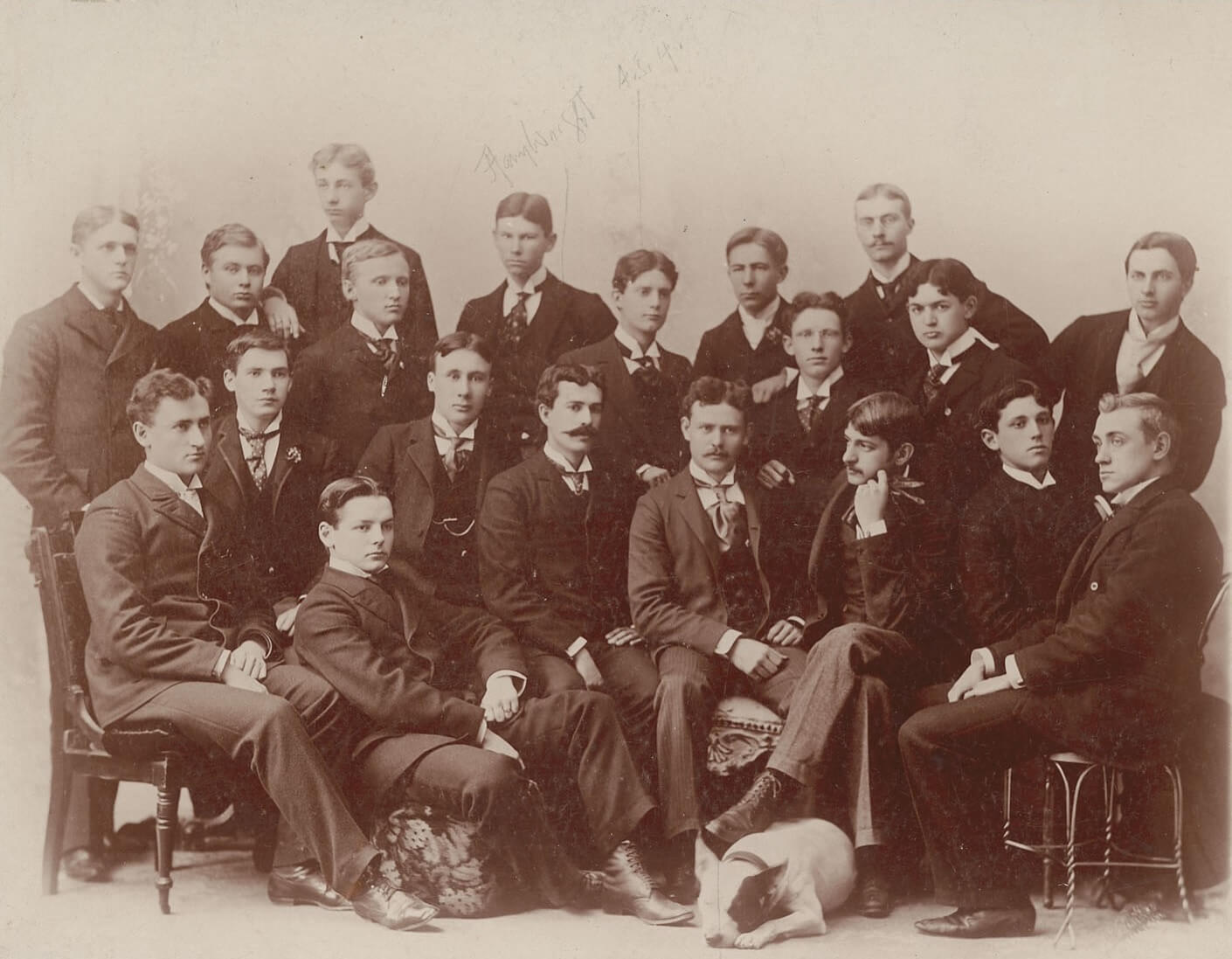

Phi Gamma Delta in 1894. Norris seated in in front row, third from right; Saying from a ritual that Norris started at his fraternity.

While at Cal, Frank Norris was a fraternity brother at Phi Gamma Delta. He left his mark on the fraternity by establishing the "Pig Dinner" tradition, which soon spread to other chapters.

The origin of the Pig Dinner started with a prank, where Norris' fraternity brothers released a squealing pig to mock the campus glee clubs' singing abilities; then, they corralled the pig in their chapter house on Dana Street, where they performed a ceremony Norris had written.

The ceremony consisted of yelling “All Hail the Pig!” and sealing a vow of allegiance by kissing the pig's snout.

These dinners became an annual tradition, celebrated on the eve of Thanksgiving and the Stanford vs. Cal game. Today, the Pig Dinner is one of the longest known celebrated traditions among fraternities.

When Frank Norris died at the young age of 32, Phi Gamma Delta paid for his gravestone in Mountain View Cemetery, and they often visit him to remember the founder of their tradition. Cemetery docent Ron Bachman says, “They always leave a bottle containing yellow-tinged liquid on the grave, but we don't recommend anyone drinking it. It's probably not what was originally in the bottle.”

The Wave, a San Francisco journal that Norris wrote for

After leaving college, Frank Norris worked as a travel writer. First, he worked for the San Francisco Chronicle covering the Boer War in South Africa, but he was deported from the country after being captured by the Boer army.

After that, he worked again for The Wave as an editorial assistant, and later, he covered the Spanish-American War in Cuba for McClure's Magazine. He joined a publishing firm in 1899, and that same year he published McTeague.

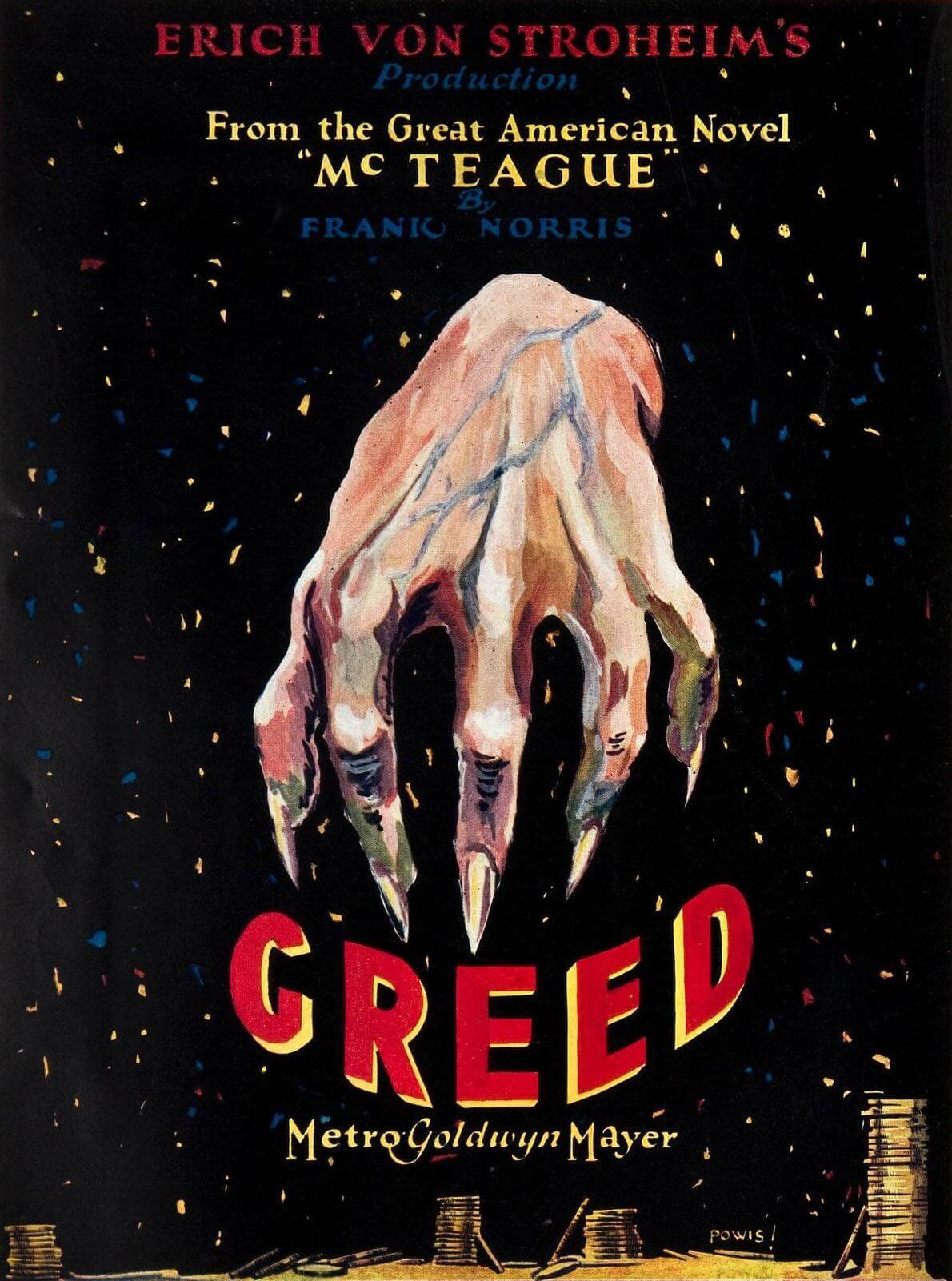

Poster for Norris' McTeague film adaption

In 1899, Frank Norris published McTeague: A Story of San Francisco. He had been working on it since 1892, during his Berkeley days. From City Lights Bookstore: “McTeague is the story of a poor dentist scraping by in San Francisco at the end of the 19th century, and his wife Trina, whose $5,000 lottery winning sets in motion a shocking chain of events.”

It explores themes of greed and human nature.

The inspiration for McTeague was likely a murder that shocked San Franciscans in 1893, combined with the interviews he conducted for The Wave during his time at Berkeley.

During this time, Frank Norris was deeply absorbed in Émile Zola's naturalist works—even referring to himself as a “Zola boy”—which influenced his work. He was also likely influenced by his Berkeley professor Joseph LeConte, a promoter of social Darwinism and eugenics.

In his own words, Norris sought to render “the unplumbed depths of the human heart" in his writings. He was not immune, though, to the negative influences that led to his writing a character that, as Harvard professor Elisa New says, is "the most apparently anti-Semitic character in American literature".

McTeague was adapted into a film, Greed, in 1924. Originally, the film had a runtime over eight hours, but, much to the director's dismay, was cut down to 140 minutes before release by MGM Studios.

The cultural influence of McTeague can also be felt on Polk Street in San Francisco at McTeague's Saloon, a bar named after Norris' classic.

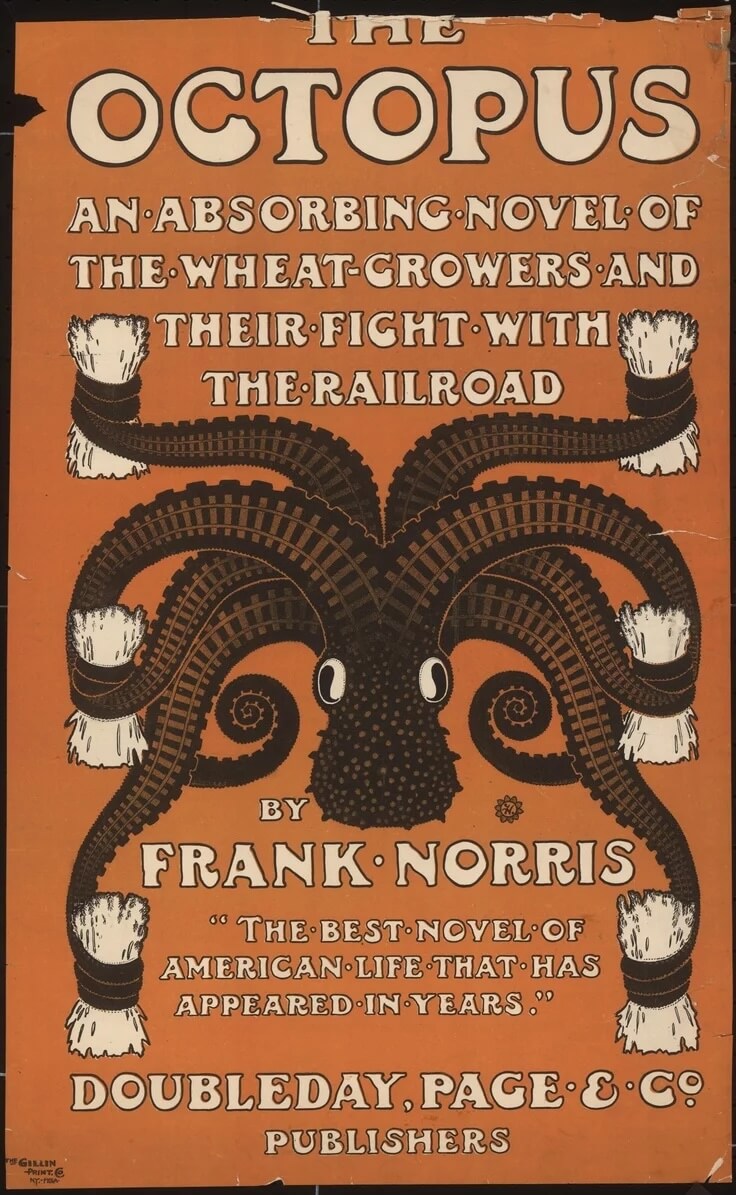

Norris' The Octopus: A Story of California

Just a couple years after publishing McTeague, Frank Norris published The Octopus: A Story of California, a novel that "examines the struggle of California wheat farmers in the San Joaquin valley against the powerful Pacific and Southwestern Railroad monopoly."

American Historian Richard White writes, “The Octopus was the literary apotheosis of the power, ruthlessness, and efficiency of the modern corporation.” The book was based on the Mussel Slough Tragedy, in which a land dispute between Southern Pacific and local settlers erupted in a gun battle, leaving seven dead.

Portrait of Frank Norris

“It was thus he became a mirror showing us to ourselves."

— Berkeley Professor George Cunningham Edwards

Frank Norris' The Octopus was meant to be part of a trilogy, titled The Epic of the Wheat; however, Norris died in 1902, just a year after publishing The Octopus. The second book was published posthumously.

Frank Norris passed away due to peritonitis from a ruptured appendix, leaving behind his new wife and baby. He was 32.

In a tribute from Berkeley faculty members, Professor Thomas Rutherford Bacon recalls Norris as an average student, but “what distinguished him...was his unfailing confidence that he had the capacity for literary success in him, and his dogged determination to bring it out, using all possible means to that end.”

Norris' algebra professor (another math class Norris failed) wrote, "[Norris] was a keen observer of men and women as he saw them and interpreted their lives—their longings, their foibles, their loves, their truthfulness and their shams. It was thus he became a mirror showing us to ourselves."

Sources

- Frank Norris: The Writer Who Couldn't Make the Numbers Add Up by Deanna Paoli Gumina

- Portrait of Frank Norris at 10 years old

- Delta Xi chapter, UC Berkeley

- Frank Norris Pig Dinner

- 1895 The Wave

- Frank Norris (1870-1902) - Noted Author by Michael Colbruno

- McTeague by Frank Norris by Peter A. Brier

- Frank Norris's McTeague: Naturalism as Popular Myth by Donald Pizer

- McTeague: A Story of San Francisco

- Greed (lost 8-hour cut of drama film; 1924)

- My Favorite Anti-Semite: Frank Norris and the Most Horrifying Jew in American Literature by Elisa New

- Britannica | The Octopus

- Richard White on Frank Norris, The Octopus, and the Southern Pacific Railroad

- Wikipedia | The Octopus: A Story of California

- The Tangled Tale That Inspired a Muckraker by Cecilia Rasmussen

- A Note on Frank Norris' Death: Berkeley Faculty Members Pay Tribute by Jesse S. Crisler