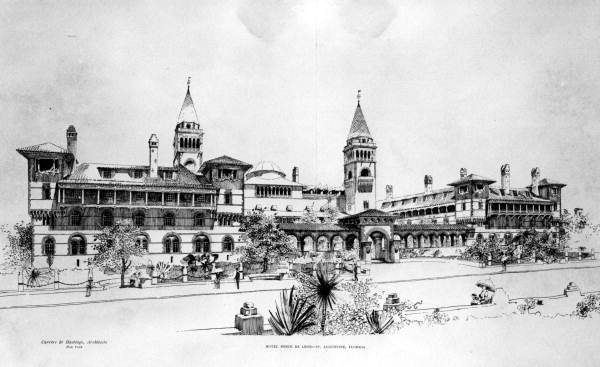

Ponce de Leon hotel in St. Augustine, Florida, which Maybeck worked on early in his career

Bernard Maybeck was born in New York City in 1862 to German immigrant parents. While in college in New York, Maybeck picked up his father's trade of high-quality woodcarving, but he soon discovered his passions lie in design.

At age 19, Maybeck's father sent him to Paris to work alongside furniture makers. Close by was the École des Beaux-Arts, an architecture school, and Maybeck decided to enroll.

Maybeck finished his coursework in 1886 (though at the time foreign students were not allowed to receive a degree, a rule that changed just a year later) and returned to the U.S.

He worked for architects in New York, contributing to notable projects like Henry Flagler’s Hotel Ponce de Leon in St. Augustine, Florida; later, he moved to Kansas City, but he didn't stick around for long. He met his wife, Annie, in Kansas, and then they moved to the Bay Area in 1890.

The Maybeck house in 1902, seen from the rear

Bernard Maybeck found stable employment as an instructor at Cal in 1894, teaching descriptive geometry and, later, architecture courses. When he first started, though, a school for architecture did not exist, so he taught interested students – like Julia Morgan – out of his home.

Maybeck's house was both a classroom and a lab; students learned design theory and practical application, where pupils actually built additions for Maybeck's house. He urged the most promising ones to continue their studies at the École des Beaux-Arts, and some of them did.

“A house should fit into the landscape as if it were a part of it, it should also be an expression of the life and spirit which is to be lived within it.”

— Bernard Maybeck

Maybeck's first client was his eccentric friend and poet Charles Keeler, whom he met on the ferry to San Francisco. Both were intensely dedicated to their architectural and artistic visions, primarily believing that “a house should fit into the landscape as if it were a part of it.” He achieved this by using unpainted redwood, windows reaching the roofline, and configuring the house so that it hugs that hill, all to create an embedded, natural feeling.

Maybeck designed the “Gothic House,” as he called the homes he built of this style, free of charge – he wanted this design to set an example for the community.

The Keeler house design was a novel idea at a time when San Francisco was mass-producing row houses and Italianate mansions dotted the shores of Lake Merritt. Over the next few years, Maybeck would design half a dozen more homes in this style.

Maybeck, Keeler, and their neighbors founded the Hillside Club in 1898 to see to it that their neighborhood was designed to their “woodland garden” tastes.

After Maybeck built Keeler's house, Keeler feared that the neighborhood would be “completely ruined when others [came] and [built] stupid white-painted boxes all about.”

Maybeck advised him, “You must see to it that all the houses about you are in keeping with your own,” which pushed Keeler to recruit friends to buy the neighboring plots of land and build homes that fit the Hillside design specifications.

The Faculty Club, originally designed by Bernard Maybeck

In 1902, Bernard Maybeck designed the Faculty Club, which at the time was just a one-room clubhouse to be expanded on later by campus architect John Galen Howard.

Maybeck designed the “Gothic House,” as he called the homes he built of this style, free of charge – he wanted this design to set an example for the community.

According to the UC Berkeley website, the building is “considered an architectural snapshot of the Arts and Crafts movement,” a period that saw designers seeking to improve standards of decorative design, which was believed to have been debased by mechanization. The Faculty Club is listed internationally as one of the finest examples of American Craftsman design. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Maybeck's influence on Berkeley's campus can be seen at the Faculty Club and the Women's Gymnasium, which Maybeck designed in 1925 with Julia Morgan.

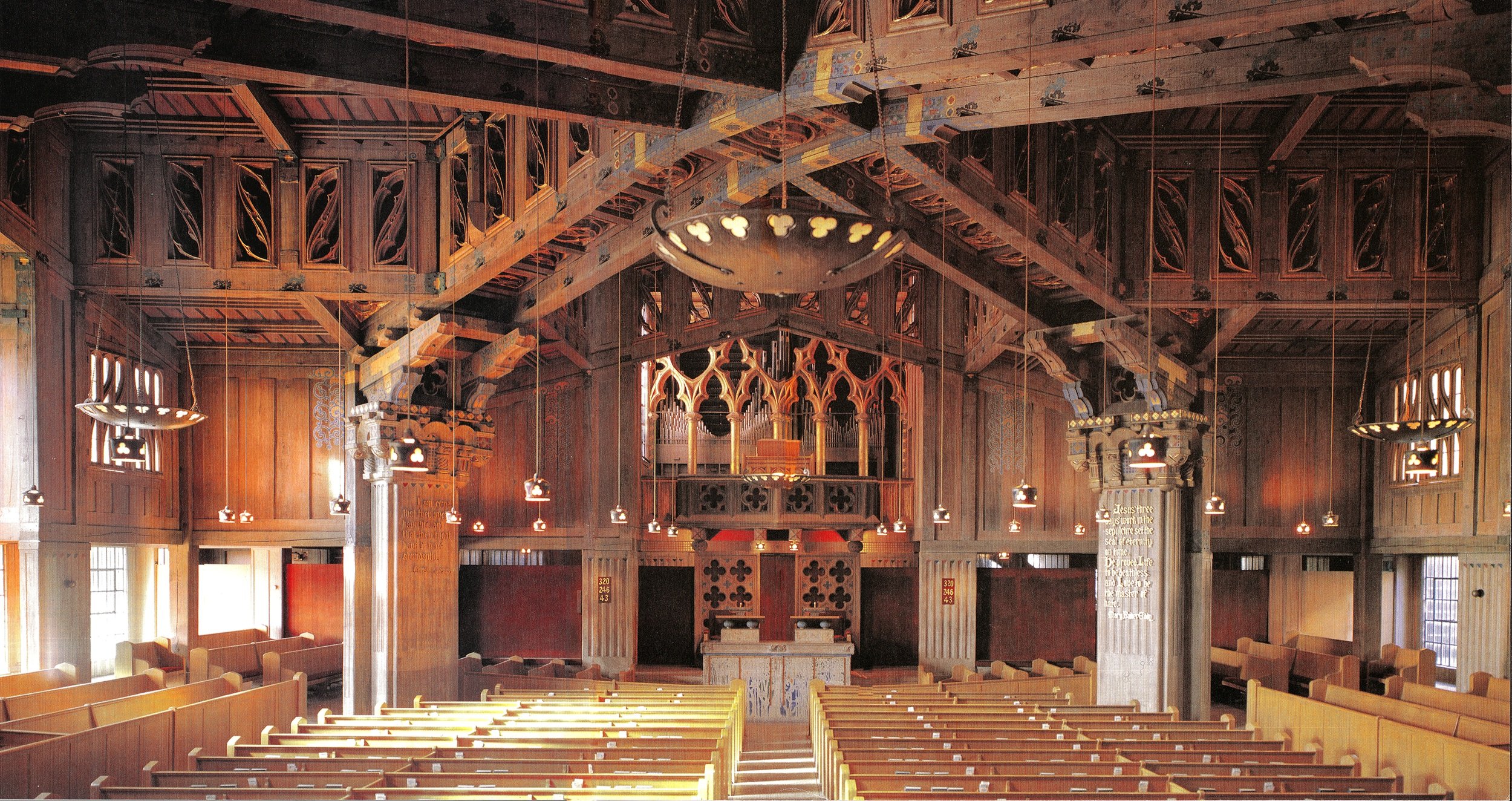

First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Berkeley, designed by Bernard Maybeck

In 1910, Bernard Maybeck was commissioned to build the First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Berkeley. This would be his first acclaimed success, with some critics dubbing it the “most significant ecclesiastical building in the United States.”

The building is “mysteriously compelling...human in scale but exhilarating in spiritual grandeur” and mixes many different influences.

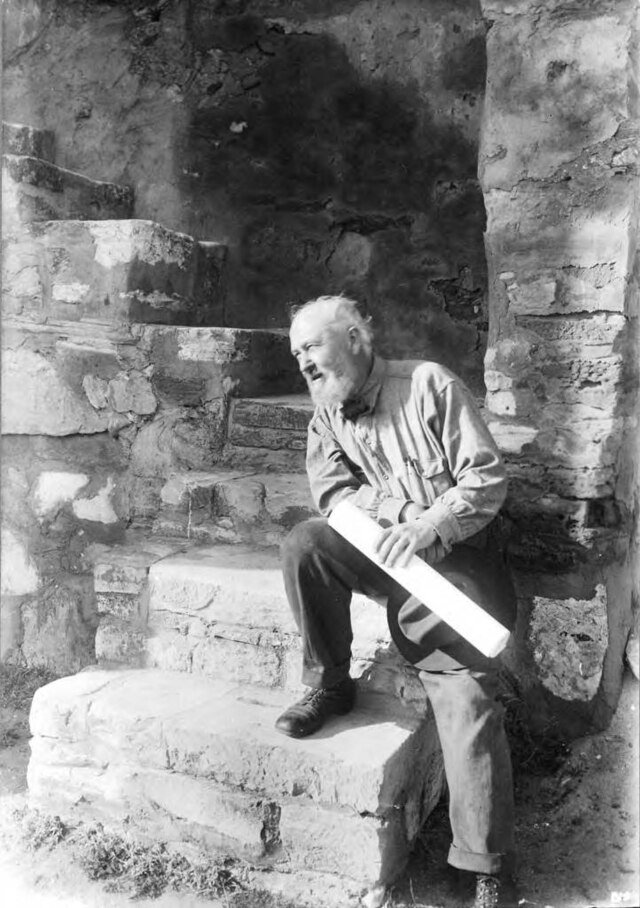

Despite the church's success, Maybeck's career went through a slump in the period after. Work was spotty, and Maybeck was “an indifferent salesman.” One critic remarked that, though he regarded Maybeck as a genius, he was not regarded as a successful architect. “His Diogenes-like view of life was against it. He hated contracts, estimates, and all the rest of the business side of architecture.”

San Francisco Palace of Fine Arts

During a slump in his career, Maybeck found stable work with an old friend, Willis Polk, an architect in San Francisco. Polk was chairman of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition's architectural commission, and he was in charge of designing the most important building: a gallery for the paintings and sculptures.

Polk conducted an in-house competition for designs, and Bernard Maybeck submitted a charcoal sketch of a “lonely, vaguely classical building that looked like one of Piranesi’s drawings of the ruins of Rome” seated at the edge of a lagoon. Dazzled by the idea, Polk and his staff selected Maybeck.

Maybeck's Palace of Fine Arts appeared to be “a Greco-Roman temple in a state of decay [...]. This, he thought, was an appropriate state of mind for persons who were about to enter a treasury of art. On every side there were reminders that empires wither, buildings crumble, idols fall, and that the carefully drawn lines of architects are rubbed away by ineluctable hands. Beauty alone endures.” The Palace was a triumph.

Though originally built as a temporary structure for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, the Palace's popularity prompted the city and a wealthy donor to tear down the temporary structure in 1957 and reconstruct the Palace from Maybeck’s original plans.

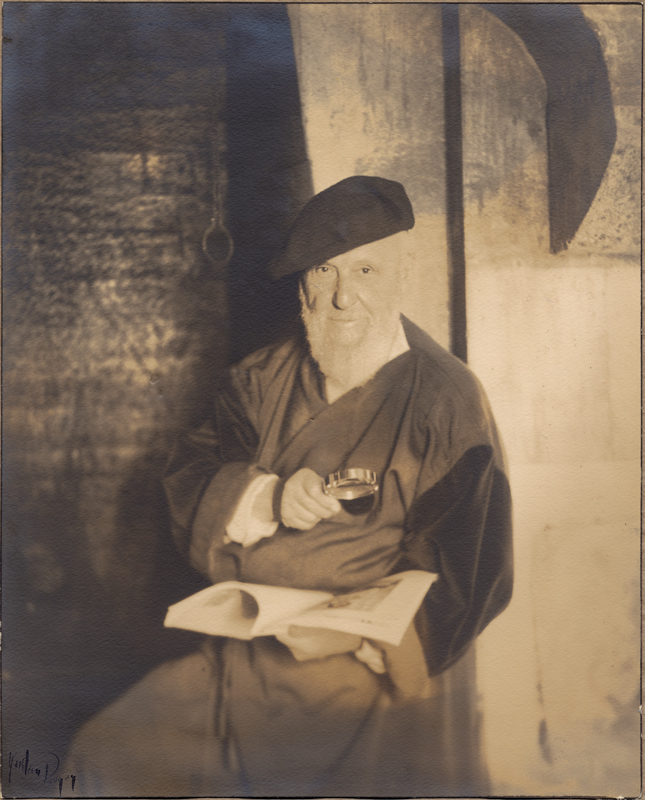

Bernard Maybeck in 1919

Bernard Maybeck's office stayed busy following the Palace of Fine Arts' success, designing houses, studios, college campuses, hotels, and town plans.

Reflecting on Maybeck's legacy, author Richard Reinhardt writes, “In truth, there was a constant element, running like a tightly braided thread through all of Maybeck’s work. It was the element of spirituality. For Maybeck was at heart a Platonist, a believer in abstract virtues—goodness, beauty, truth—which he found as readily in the textures of a piece of wood as in the soul of a human being.”

Sources

- Maybeck, Bernard (1862-1957)

- Lives of the Dead at Oakland's Mountain View Cemetery by Dennis Evanosky and Michael Colbruno, p. 37

- Bernard Maybeck by Richard Reinhardt

- Maybeck's first house was a design laboratory by Daniella Thompson

- History of the Hillside Club

- Faculty Club, University of California

- The Faculty Club, University of California, Bernard Maybeck

- The Faculty Club | History

- The Arts and Crafts Movement in America by Monica Obniski

- Friends of First Church Berkeley

- Palace of Fine Arts - Photo

- Everything You Never Knew About San Francisco's Palace Of Fine Arts by Jamie Ferrell

- Wikipedia | Bernard Maybeck