“My father used to say, ‘Get an education. It's the one thing the white man can't take from you.’”

— Ida Louise Jackson in an interview with the Oral History Center at Berkeley

Ida Louise Jackson demonstrated academic excellence from the time she was three, when she first started reading.

At the young age of fourteen, she graduated high school; shortly after, she graduated from college with a Normal Teaching Diploma.

Jackson grew up in Vicksburg, Mississippi, but in 1918, she and her mother followed Ida's brother out west, under the impression that California would have more opportunity and racial equality.

When Jackson moved to the Bay Area, she enrolled in UC Berkeley and received her Bachelor's degree, and when she was rejected from a teaching job by the Oakland Public School system, she went back to Cal and got her Master's. She was one of 17 Black students at Cal.

In an interview with Berkeley's Oral History Center, she emphasized the importance her mother and father placed on receiving an education as a means of broadening her opportunities in a prejudiced system.

Indeed, it was a prejudiced system Jackson was up against—after receiving her Master's, the Oakland schools still rejected her, this time saying she needed more experience. She instead taught in El Centro, becoming the first Black woman to teach high school in California.

“Where a door was shut in their face, they opened their own.”

— Berkeley Historian Gia White

While a student at Cal, Ida Louise Jackson founded the Rho Chapter of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, creating a community for the small group of Black women students.

This photo, which depicts Jackson sitting in the middle, cost a whopping $45, or $600 today, to put in Cal's yearbook.

However, when the yearbook came out, AKA's photo wasn't there. They went to President Barrows' office to find out why, and he answered by telling them they “weren't representative of the student body.” Jackson said "neither the sorority pictures nor the individual senior pictures of most Black students made the yearbook."

As pointed out by Gia White, Berkeley faculty member and historian, Jackson's AKA chapter was “a sisterhood that would splinter at times and suffer painful losses, but also have incredible victories. [...] Where a door was shut in their face, they opened their own.”

Among these incredible victories were the mobile health clinics Jackson went on to open with AKA in Mississippi.

Report for the Mississippi Health Project in 1935, an initiative started by Jackson

Though Ida Louise Jackson left the South when she was a teenager, she never left behind her vision to uplift the Black community of her home state, Mississippi.

When Jackson later became National President of Alpha Kappa Alpha in 1933, she made it her mission to do just that. According to the report depicted, Jackson "travelled three thousand miles across America to tell the [Alpha Kappa Alpha] national organization in New York...of the woeful neglect of lower class Negroes in the deepest South [...]. She challenged the entire sorority to motivate its ideal of raising the social status of the Negro."

Jackson focused her initiative on assisting educators in rural Mississippi, stating that she believed “if the teachers were better prepared then they could inspire the youth to go ahead and get an education.”

From this project sprung the Mississippi Health Project, a decade-long initiative to bring basic healthcare to children and adults in rural areas.

Mississippi Health Project staff in 1937

Though it originally started as an education project, Jackson quickly realized that students also lacked basic healthcare and expanded the project to include child health care centers.

Throughout the project, Jackson cleverly solved any challenges thrown her way; for instance, when it became difficult for children to travel to the clinic, she adapted the health care center to be mobile, travelling between the rural areas.

Later, she again expanded the program to include adults.

Over the course of a decade, Jackson's program immunized over 14,500 children against diphtheria and smallpox. In 1934, Jackson was invited to the White House twice by the Roosevelts. On her second visit, Eleanor Roosevelt became an honorary member of Alpha Kappa Alpha.

Prescott School, where Jackson became Oakland's first Black teacher

Oakland schools first denied Ida Louise Jackson stating that she was inexperienced; then, when she reapplied after obtaining her Master's, they denied her again.

Despite her outstanding credentials, Jackson could not find employment in the East Bay. She accepted a job in El Centro, making her the first Black woman to teach high school in California.

After she garnered experience in the El Centro schools, Jackson re-applied and became the first Black woman to teach in Oakland.

A group formed to protest Jackson's appointment, but Jackson was unphased. In an interview, she said, “Well...I was interested primarily in teaching and children. So whatever efforts were made to make my life uncomfortable, it didn't register. I was determined. It was a challenge.”

Jackson's students loved her and even brought her flowers.

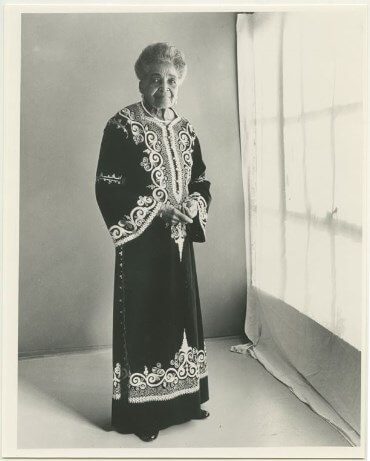

Ida Jackson circa 1980s; Jackson retired on her sheep farm in Mendocino

While Ida Louise Jackson was teaching in Oakland schools, her brother Emmett purchased a 1,280-acre sheep ranch in Mendocino and made her co-owner.

She wanted to become a school administrator, but despite her 30 years of experience, she was consistently denied opportunities to move up due to racism in the school system.

In an interview, she explains, “You see, California hasn't proved to be the Mecca that most of us thought it was. To put it roughly, the black could go to the shows and sit anywhere they wanted to. [...] But when it came to equality of opportunity in employment, jobs above the average, the racial factor entered. It has never disappeared.”

She recounts her brother Emmett saying, “Sister, you will never be anything but a teacher in Oakland. So why waste your time there?” Soon after, she decided to work full-time managing the ranch, which she enjoyed and described as a beautiful place.

Later, Jackson donated her ranch to UC Berkeley specifying that the proceeds go toward scholarships for Black graduate students at Cal.

Ida Louise Jackson Graduate House

Today, Ida Louise Jackson is remembered by the graduate house in her namesake, which Cal named after her in 2004. The UC Berkeley website says: “The [Graduate House is the] first building at UC Berkeley named for an African-American woman — Ida Louise Jackson, daughter of a slave and pioneering educator in both California and her native Deep South.”

Sources

- Remembering Ida L. Jackson by Sean Dickerson

- As I Walk these Paths: Honoring the Unheralded Courage of the African American Women Pioneers of the University of California, Berkeley by Gia White

- Ida Louise Jackson: Overcoming Barriers in Education by Ida Louise Jackson and Gabriella Morris

- Mississippi Health Project Annual Report No. 2 by Alpha Kappa Alpha

- The Fighting Spirit of Ida Louise Jackson by Deborah Qu

- Alpha Kappa Alpha | Former International Presidents

- The Mississippi Health Project II: AKA Revisits Its Model for Community Health Care

- You Should Know About Ida Jackson by Ashawnta Jackson

- Ida Louise Jackson Graduate House